Why Health Care Staffing Crisis Persists Despite Returning to Pre-Pandemic Employment Levels

The American health care system has finally regained the jobs it lost at the onset of the pandemic, but the industry faces a continued uphill battle to bring the next generation of health care workers into the fold. Incredible Health charted Bureau of Labor Statistics data on employment trends in health care and social assistance, referencing surveys and news reports to describe the trends behind them. Around 4 million nurses serve as the backbone of the health care system; they consistently rank as the most-trusted profession in the U.S. Against all odds, they earn that trust while battling subpar working conditions that threaten their ability to do their work. Survey results reveal stagnant pay and long work hours have made it increasingly difficult for nurses to continue in the field, which is all the more problematic as the staffing shortage persists.

The American health care system has finally regained the jobs it lost at the onset of the pandemic, but the industry faces a continued uphill battle to bring the next generation of health care workers into the fold. Incredible Health charted Bureau of Labor Statistics data on employment trends in health care and social assistance, referencing surveys and news reports to describe the trends behind them. Around 4 million nurses serve as the backbone of the health care system; they consistently rank as the most-trusted profession in the U.S. Against all odds, they earn that trust while battling subpar working conditions that threaten their ability to do their work. Survey results reveal stagnant pay and long work hours have made it increasingly difficult for nurses to continue in the field, which is all the more problematic as the staffing shortage persists.

And an aging American population faces a harrowing proposition: Without more support for health care workers, the high quality of care Americans expect may simply just diminish. That’s according to the former president of the American Nursing Association, Ernest Grant, an RN with a doctorate in nursing, who addressed the staffing crisis in a U.S. News and World Report panel. Warnings about a shortage of health care workers “started maybe 15-20 years ago,” Grant said. “It’s going to be the consumer that’s going to be impacted,” Grant added. “Things that could’ve been avoided or picked up on … because of how overworked staff may be, they may get overlooked.”

The current health care staffing crisis trajectory also risks making medical care more expensive. Some of the obstacles begin before professionals even enter the workforce.

EMPLOYMENT IN HEALTH CARE HIT NEARLY 21 MILLION IN DECEMBER The U.S. population is getting older and requires more health care resources than ever before. The BLS projects health care and social assistance jobs will grow more than any other workforce sector from 2021 to 2031. And it forecasts that jobs caring for the elderly will drive most of that growth. Grant, now an educator at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill School of Nursing, pointed out the need for more resources to support health care educators in the higher education system—where too few instructors mean fewer well-trained graduates each year.

For instance, Houston Methodist has embedded its own nursing educators in local nursing schools to help fill in where there are gaps in faculty, Gail M. Vozzella, the hospital’s senior vice president and chief nursing executive, told the U.S. News panel. In short, the need for nurses is growing faster than schools can train students.

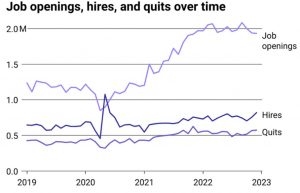

JOB OPENINGS IN HEALTH CARE HAVE FAR SURPASSED PRE-COVID LEVELS The gap between the number of health care workers the country needs vs. how many are hired is evident in ballooning job openings. During the largest waves of COVID-19 patients, many states turned to the National Guard and other service members to temporarily staff hospitals and administer vaccines. It was an unusual turn for troops more used to serving overseas or, when in the U.S., helping with situations like hurricane recovery and civil unrest. Today, nurses describe the staffing shortage as creating ongoing difficulties with their jobs, including high stress levels, exhaustion, and burnout. Nearly 30% of early career nurses—those with less than 10 years of experience—reported to the American Nursing Association their well-being is suffering because of their jobs.

Even before COVID-19 arrived, nurses were leaving their jobs in droves, citing overwork and abuse in the workplace. In a 2019 survey of registered nurses conducted by AMN Healthcare, 44% said they often considered quitting their jobs.

JOB OPENINGS GREW OVER TWICE AS MUCH AS HIRES SINCE 2019 Like a leaky bucket, health care institutions have lost workers over the last three years at greater rates than they can hire. And when nurses disappear from jobs at any of the nation’s more than 6,000 hospitals, their institutional knowledge and the clinical expertise they’ve built up disappears with them, experts warn. “The good part—if there is a good part of a crisis, which I believe there always is—is it allows us to look carefully at the work of the nurse and we have a spotlight nationally,” Vozzella said.

(This story originally appeared in The Sacramento Bee.)