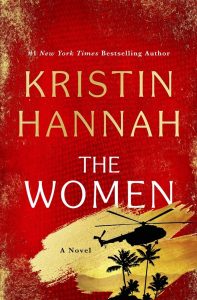

Kristin Hannah’s Next Book Focuses on Volunteer Nurses During Vietnam War

Kristin Hannah has taken readers to the depths of the Alaskan wilderness (“The Great Alone”), World War II in France (“The Nightingale”), the Dust Bowl (“The Four Winds”)and decades in two women’s friendship (“Firefly Lane”), among others.

Kristin Hannah has taken readers to the depths of the Alaskan wilderness (“The Great Alone”), World War II in France (“The Nightingale”), the Dust Bowl (“The Four Winds”)and decades in two women’s friendship (“Firefly Lane”), among others.

For her next book, “The Women,” out Feb. 6, 2024, Hannah is focusing on a moment in history most are familiar with — but providing perspective most aren’t.

“The Women” focuses on women who volunteered as nurses during the Vietnam War. Speaking to TODAY.com, Hannah says, unlike past historical novels, she has a personal connection to this era.

“I have wanted to write about this moment in time because I remember my friends’ dads not only going off to war, but how they were treated when they came home, and what a difficult time that was,” she says.

At this point in her decades-long career, she says, “I finally got old enough to feel confident enough to take on such a big, complex issue.”

Hannah’s historical novels tend to explore notable moments in world history from women’s points of view. This, she said, was one that she felt was urgent to tell. “I wanted their story to be told,” she says.

“These gals went over raised on patriotic stories of WWII and of their father’s service. They go to Vietnam and experience horrible conditions, as well as amazing camaraderie and growth. Then, they come home and are forgotten,” Hannah says.

For the novel, she interviewed several former Vietnam nurses, as well as a dustoff pilot, who took the wounded from the fields and brought them to the hospital. Hannah says that much of the stories from Vietnam were clouded by the war’s political connotations — but that “it’s time that people understood what the women were doing.”

Hannah’s protagonists are always in daunting and trying positions — ones that she tries to imagine herself in. When it comes to “The Women,” she doesn’t think she’d last as long as her characters.

“I am pretty sure that I would have not been tough enough or strong enough to do this. That’s what I admire so much about them. Not only were they under fire and living in war conditions. But in talking to them, (hearing) their compassion and their caring, talking to the men who were saved by them and how they felt — it’s just remarkable,” she says.

Read an excerpt of ‘The Women’

When Frankie woke, the airplane cabin was quiet except for the hum of the jet engines. Most of the window shades were drawn. A few overhead lights cast a gloomy glow over the men packed into the jet.

The loud razzing, the laughter, the horseplay that had marked most of this flight from Honolulu to Saigon was gone. The air seemed heavier, harder to draw into her lungs, harder to expel in an exhalation. The new recruits—recognizable by their still-creased, new green fatigues—were restless. Unsettled. Frankie saw the way they looked at each other, their smiles bright and brittle. The other soldiers, those weary-looking men in their worn fatigues, men like Captain Bronson, sat almost too still.

Beside Frankie, the captain opened his eyes; it was the only change in him from sleeping to awake, just an opening of his eyes.

Suddenly the plane lurched, or bucked, seemed to turn onto its side. Frankie cracked her head on the tray on the back of the seat in front of her as the plane nose-dived. The overhead bins opened; dozens of bags fell out into the aisle, including Frankie’s.

Captain Bronson put his rough, gnarled hand on hers as she clutched the armrest. “It’ll be okay, Lieutenant.”

The plane stalled, steadied, lurched upward into a steep climb. Frankie heard a pop and something cracked beside her.

“Is someone shooting at us?” Frankie said. “Oh my God.”

Captain Bronson chuckled. “Yeah. They love to do that. Don’t worry. We’ll just circle around for a while and try again.”

“Here? Shouldn’t we go somewhere else to land?”

“In this big bird? Nope. It’s Tan Son Nhut for us, ma’am. They’ll be waiting on the FNGs we got on board…”

He smiled. “And one beautiful young nurse. Our boys’ll clear the airport in no time. Not to fret.”

The plane circled until Frankie’s fingers ached from the pain of her grip on the armrests. Outside, she saw orange and red explosions and streaks of red across the dark sky.

Finally, the plane evened out, and the pilot came on the loudspeaker to say, “Okay, sports fans, let’s try this shit again. Buckle up.”

As if Frankie had ever unbuckled her seat belt.

The jet descended. Frankie’s ears popped, and the next thing she knew, they were thumping onto the runway and powering down, rolling to a stop.

“Senior officers and women disembark first,” sounded over the loudspeaker.

The officers waited for Frankie to exit first. She wished they hadn’t. She didn’t want to be first. Still, she grabbed her travel bag from the aisle and slung it—and her purse—over her left shoulder, leaving her right hand free to salute.

When she exited the aircraft, heat enveloped her. And the smell. Good Lord, what was it? Jet fuel . . . smoke . . . fish . . . and honestly there was a stench of something like excrement. A headache started to pulse behind her eyes. She made her way down the stairs, where a lone soldier stood in the darkness, backlit by ambient light from a distant building. She could barely make out his face.

Off to the distant left, something exploded in orange flames.

“Lieutenant McGrath?”

She could only nod. Sweat crawled down her back. Were they bombing over there?

The soldier said, “Follow me,” and led her across the bumpy, pock-marked runway, past the terminal, and to a school bus that had been painted black, even the windows, which were covered in some kind of chicken-wire mesh. “You’re the only nurse arriving today. Take a seat and wait. Don’t exit the bus, ma’am.”

The heat in the bus was sauna-like, and that smell—shit and fish—made her gag. She took a seat in the middle row of seats, by a black-painted window. It felt like being entombed.

Moments later, a black soldier in fatigues, carrying an M16, climbed into the driver’s seat. The doors whooshed shut and the headlights came on, carving a golden wedge out of the darkness ahead.

“Not too close to the window, ma’am,” he said, and hit the gas. “Grenades.”

Grenades?

Frankie inched sideways on the bench seat. In the fetid dark, she at perfectly upright, was bounced up and down in her seat until she thought she might vomit.

At last the bus slowed; in the headlights’ glare, she saw a set of gates manned by American MPs, illuminated in the bus’s headlights. One of the guards spoke to the driver, then backed away. The gates opened and they drove through.

Not much later, the bus stopped again. “Here you go, ma’am.”

Frankie was sweating so profusely she had to wipe her eyes. “Huh?”

“You get out here, ma’am.”

“What? Oh.”

She realized suddenly that she hadn’t gone to baggage claim, hadn’t retrieved her duffel. “My bag—”

“It will be delivered, ma’am.”

Frankie gathered up her purse and travel bag and went to the door.

A nurse stood in the mud, dressed in a white uniform, cap to shoes, waiting for her. How on earth could that uniform be kept clean? Behind her was the entrance to a huge hospital.

“You need to exit the bus, ma’am,” the driver said.

“Oh yes.” Frankie stepped down into the thick mud and started to salute.

The nurse grabbed her wrist, stopped the salute. “Not here. Charlie loves to kill officers.” She pointed to a waiting jeep. “He’ll take you to your temporary quarters. Report to admin for in processing tomorrow at oh-seven-hundred.”

(This story originally appeared on TODAY.com.)