Nurses Shouldn’t Be Treated Like Your Mother

More than 15,000 nurses in Minnesota who staged a three-day strike this week aren’t just fighting for better pay and working conditions, they’re battling to secure public support — especially as evidence mounts that patients will die in their absence.

More than 15,000 nurses in Minnesota who staged a three-day strike this week aren’t just fighting for better pay and working conditions, they’re battling to secure public support — especially as evidence mounts that patients will die in their absence.

A century’s worth of sentimental blather about nursing as selfless women’s work has left Americans ill-equipped to grasp the severity of the current crisis, which has already fueled numerous nursing strikes before this week’s walkout. The history can help us understand why, unlike workers at Amazon.com or Starbucks Corp., nurses must confront decades of sexist attitudes that have condemned them for being anything other than tireless, self-sacrificing caregivers.

The modern nursing profession originated in the 19th century, when women volunteered to tend wounded soldiers during the Civil War. These first female forays into medicine helped pave the way for more formal nurse training schools in the decades after the war ended.

These new programs focused exclusively on training women. Though men had served as nurses during the Civil War as well, almost all the new schools refused admission to men. Nursing had become woman’s work.

Typically, hospitals would set up adjacent schools for their female students. These women received most of their training on the job in the hospitals, serving as free student labor while living as dependents in dormitories that were run like convents.

When these apprentice nurses finished their program of study after two or three years, most went into private nursing, serving individuals in the comfort of their own homes. Very few went to work full time in hospitals because most of the work there was done by students.

This arrangement helped cement a public perception that nursing was less a conventional job and career than a selfless endeavor akin to motherhood. Indeed, many left their jobs when they married and had children.

Strikes were rare. The reliance on transient, unpaid student labor kept militancy to a minimum. So, too, did the fact that the nation’s burgeoning nursing schools — nearly two thousand in number by 1929 — guaranteed a surfeit of labor. In some cities in this era, 10% of female workers listed nursing as their vocation.

All of this collapsed in the Great Depression, when most families could no longer afford private nursing. Professional associations — particularly the American Nurses’ Association, or ANA — sought to address the problem by closing substandard schools and limiting the number of students. Equally important was a campaign to have hospitals hire former private nurses as part of their permanent staff.

This reform made nursing much more like other jobs. But the ANA continued to pay homage to the principle that female nurses must be selfless, giving creatures. In 1933, it opposed the eight-hour workday, claiming that “an arbitrary limitation on the hours of work violates the whole spirit of nursing.”

The rise of a permanent, but poorly paid and overworked cadre of hospital nurses challenged this quaint notion. In 1937, the first real nurse strikes erupted in hospitals in New York and New Jersey, raising the specter of full-scale unionization.

Once again, the ANA and its allies fought these developments. An editorial published in the American Journal of Nursing in 1938 declared that “the nurse as a professional and giver of comfort is in fundamental conflict with struggling for reasonable working conditions and economic security.” Or as one pithy summary of the ANA’s position put it: “A nurses’ union would be almost, if not quite, as absurd as a mothers’ union.”

So in 1942, as World War II put unprecedented strain on nurses, state organizations took the lead, with the California State Nursing Association in the vanguard. The group became the collective bargaining agent for California’s nurses, successfully winning them a pay raise.

In the postwar era, the idea that nurses might engage in collective bargaining via state associations gained grudging acceptance, largely because the ANA found it preferable to the alternative: unionization.

Then in 1947, Congress muddied the waters when it inadvertently exempted workers at non-profits — in other words, many hospitals – from engaging in collective bargaining. The Taft-Hartley Act also meant that nurses were excluded from unemployment insurance, minimum wage laws, and disability benefits.

The second-rate status of nurses proved difficult to fix. In the popular imagination, the typical nurse was a young, attractive woman working for a bit before marriage and motherhood. It was less a job than a calling.

In reality, more women as well as some men were choosing nursing as a lifelong career. Eventually, a series of nursing strikes in the late 1960s opened the door to amending the Taft-Hartley Act, despite the fact that polls from the time found that only 29% of Americans believed that nurses should be permitted to strike. By 1974, Congress permitted nurses in non-profit settings to engage in collective bargaining.

Since that time, nursing has become much more like a conventional career and has attracted a growing number of both men and women. But not enough to satisfy demand for the work.

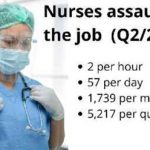

Staffing shortages and intolerable working conditions are now leading to more strikes such as the one in Minnesota. Given that people’s lives are at stake, it may prove tempting to try to force nurses back to work. But the harsh reality is that patients are going to die anyway if the nursing shortage persists. And fixing that will require a significant expansion of nursing schools, subsidies to hospitals and other financial assistance — in other words, a great deal more than appeals to imaginary incarnations of Florence Nightingale.

-Analysis by Stephen Mihm | Bloomberg

(This story originally appeared in The Washington Post.)