NJ Health Care Could Collapse If Nurses Stay Left Behind

Collapse in the next 5 years is unlikely, but the issues behind

that possibility must be addressed now, NJSNA says.

New Jersey’s health care and hospital system could collapse. And while it likely won’t occur anytime soon, reversing the possibility of collapse will require greater support for the nursing profession, according to leadership in the New Jersey State Nurses Association.

New Jersey’s health care and hospital system could collapse. And while it likely won’t occur anytime soon, reversing the possibility of collapse will require greater support for the nursing profession, according to leadership in the New Jersey State Nurses Association.

NJSNA CEO Judy Schmidt recently went to Washington, D.C., to discuss the realities nurses continue to face during the pandemic: staff shortages, higher workloads and extended shifts.

Certain conversations among nurses have become more common during the pandemic: dealing with extra work, considerations of leaving the profession and the increasingly realistic possibility of the hospital system crumbling, Schmidt says.

“I hate to be very negative,” Schmidt told Patch. “There is a potential to have a collapse of health care. Is that going to occur in the next five years? I extremely doubt it. But there’s a good possibility that if we don’t change the direction of what’s happening in the health care environment, there could be a big collapse for care in hospitals.”

New Jersey’s issues with building a nursing workforce preceded the pandemic. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services predicted that New Jersey would have one of the nation’s worst nursing shortages in 2030. The agency projected a workforce of 90,800 registered nurses in New Jersey, when the state will need 102,200 at that time.

The percentage of unfilled positions for registered nurses in New Jersey hospitals increased 13.4 percent last year, according to the New Jersey Hospital Association.

Schmidt sees a vicious cycle: experienced nurses leave the profession because of stress and overwork. Younger, talented candidates see that and opt for different jobs. And a lack of nurses means a lack of faculty for nursing schools, the CEO of the advocacy and lobbying organization says.

Hospital administrators and workers have devised solutions to ensure patient care doesn’t fall behind, but Schmidt warned that they’re only temporary fixes. Hospitals have filled shortages with agency nurses, who typically make more money than full-time staff. Additionally, nurses have been taking on extra hours and shifts, which as taken a toll. Two-thirds of registered nurses younger than 35 have reported feeling burnt out, according to the American Nurses Association.

“Right now, we’re biding our time, because the hospitals are bringing in agency support and the nurses are certainly volunteering to do extra time,” Schmidt said. “But how long will that happen? It’s not sustainable.”

Nurses around the nation have expressed similar feelings. About 15,000 nurses in Minnesota walked off the job Monday, marking the largest strike of private-sector nurses in U.S. history. The Minnesota Nurses Association planned a three-day strike to fight for better staffing and better care for their patients, according to the union.

Nursing shortages in New Jersey haven’t significantly impacted patient care yet, according to Schmidt. One key difference is that before the pandemic, nurses and medical personnel would conduct hourly rounding — scheduled visits to rooms with hospitalized patients. Few hospitals in New Jersey have been able to fully maintain this practice, Schmidt says.

But that could change if the delicate situation gets worse.

“I don’t see any negative recourse in an increase in patient falls or increase in infection rates,” Schmidt said. “But I do think we’ll start to see them as time goes on. When we can’t afford to fill these positions, when hospitals can’t afford to pay top dollar for either overtime or agency nurses coming in, then you’re going to start to see the direct impact on patient care.”

Politicians and regulatory agencies must come up with solutions to the nursing shortages, Schmidt says. While in Washington, the NJSNA’s contingent met with five members of New Jersey’s congressional delegation: Sens. Bob Menendez and Cory Booker (both D) and Reps. Jeff Van Drew (R, NJ-2), Bonnie Watson Coleman (D, NJ-12) and Andy Kim (D, NJ-3).

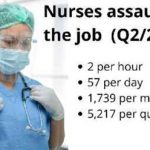

Politicians’ actions will speak louder than words, Schmidt says. But the solution will also require the public to hold more respect for nurses. Nurses are more likely to get assaulted on the job than police or prison guards, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration reported in 2017.

State lawmakers passed the Violence Prevention in Health Care Facilities Act in 2008, which required health care facilities to establish a violence-prevention program designed to protect their workers.

“Shockingly, the NJ Department of Health has failed to conduct any outreach to either employers or employees to inform them of their rights and responsibilities under the law. No surprise then that an informal survey of hospital staff HPAE conducted in 2013 found fewer than 50% of the respondents reporting their hospital was in full compliance with the law.”

The issue worsened during the pandemic, with New Jersey hospitals reported 10,000 incidents of workplace violence against their employees last year. Overall, violence against the state’s hospital workers increased by 14.6 percent from 2018-21, according to the New Jersey Hospital Association.

New Jersey stiffened penalties — including potential prison time — for people who attack health care workers. But Schmidt sees plenty of work to do in addressing the issues pushing nurses out of the profession.

“We’re always the health care heroes when there’s a pandemic,” Schmidt said, “but what about today?”

(This story originally appeared Patch NJ.)